Classical Education is the best school model available to us, both for primary and secondary schooling. It is pedagogically correct: it agrees with what we know from the science of learning, it is a ‘philosophically sound’ approach, and its methods have been tested and proven across the ages. Throughout the history of our western civilizations, successful educational practices have been based on this ‘Classical’ model.

We should imitate our ancestors in these practices, because where we have seen a significant deviation from this model, it has been detrimental to the quality of our schools.

My claim here is a very bold one and it will require a lot of explanation and support before it stands. Stay with me and I will develop the argument for Classical Education across a series of forthcoming essays. For today though, the first thing we need to establish is: What is Classical Education, and if it’s so great, how come you haven’t heard (much) about it before?

What is it?

In one sense Classical Education is just a new name for an old game. It refers to a distilled version of traditional European educational practices. When we look back at the history of education - from the ancient Greeks, to the Roman, the Byzantines, the Middle Ages, and up to the early 20th century - we can see a general form of what constituted school education. We are speaking here about primary and secondary level schooling.

Despite the many differences of these western societies across time, there can still be discerned a common strand in how they educated children. The pedagogy of each era and place had its own particular characteristics of course, but the key essential elements and structure were common to them all.

This pedagogical unity existed until c.a. the 19th century when (what is called) the progressive movement in education began gaining prominence. It brought with it significant fundamental shifts – both in how we understand education and how we practice it. Consequently, over the last two centuries we have been seeing an essential restructuring of pedagogical practices. Today we can see the reach of the progressive movement in almost every part of education in the west. In the past few decades these alterations have accelerated, with some countries replacing traditional educational practices entirely with progressive ideas.

Classical Education refers to a restorative reparative movement that in the main does not see these changes as positive. The drastic collapse of the school system’s ability to achieve its aims that can be observed across several western countries is largely attributed (by the adherents of the Classical movement) to the changes to our systems brought by the progressive movement. Classical Education, in seeking to correct course, looks to the past to learn from the educational practices predating the prevalence of progressivism. It considers that we can learn from the wisdom of our ancestors, and that we can accomplish the improvements that our schools need by using processes that have been proven to work for millennia.

The project of re-establishing traditional foundations to education involves pedagogical thinkers (like yours truly) in three main tasks:

1. The Classical Education movement carries out historical analysis to discern what traditional educational systems were. We study the history of education to understand past educational models, and to derive learning from them. You could say that: we mine the past for precious gems. Or, that we excavate the past to gain knowledge about it and from it.

Retrieving knowledge from the past also involves a process of distilling. As you can imagine, in educational practices across various locales and over thousands of years several particular variations can be found. The retrospective observer needs to sort through these and identify the key principles of traditional pedagogies.

2. Our second task is to translate findings into useful content. It is not possible to merely transplant historical educational practices into our own times and societies because education always has many ‘localised features’. There is a need to understand the essence of traditional education and to translate it into a contemporary model fit for our own days. We want to retrieve the key principles that give traditional education its greatness and effectiveness, but we want to apply these in a discerning manner.

A ‘theoretical conversation’ takes place between ‘past systems’ and ‘present situations’. (If you are interested in an example of this, I am involved in adapting the classical model for modern day Scotland. Read all about it.) We compare and contrast traditional and progressive approaches to education to do justice to the wisdom contained in both, and to hammer out the modes that are most applicable to our specific situations.

3. Thirdly, we need to draw attention to the strengths of Classical Education. These are many and well evidenced, nevertheless, they are not obvious. Progressive educational theory which has grown as a reaction to traditional education has spent the past two centuries criticising traditional models and trying to replace them, so that many of us have lost sense of the real value of the wisdom of past systems.

So in answer to the question ‘why have you not heard much about Classical Education before’: You have heard about it. Classical Education is just a new name for what education has always meant (until relatively recently). However, since we (and many of our parents) were educated in the era of progressive education, we tend to have only vague notions about the classical model.

Key Pedagogical Principles

So, what are these key principles that constitute classical education that we are looking to reinstate in education today? To understand the Classical model of education let us look at three aspects:

- its purpose,

- its content and

- its methodology.

As you will see these three aspects are inextricably intertwined, since methodology and content together flow out of the purposes of the pedagogy. Everything I refer to here needs to be expounded separately in its own paper but as a start we will give a general overview of the elements of Classical Education.

Purpose

‘The ancients believed that true happiness comes from a life well-lived, and is the result of a foundation of virtue and knowledge’

- CS Lewis -

Classical education seeks to educate children to become fulfilled people who ‘live well’ and who bring benefit to their communities by participating in them productively, responsibly and virtuously. Its purpose is to raise well-rounded virtuous people, who are civically minded, and have the intellectual training to achieve great things. It aims to inspire students to become the best they can be, whilst crucially also equipping them with the skills to be happy.

Happiness here means that the person is helped by their education to be virtuous, useful to their community and able to employ their intellectual and artistic abilities. Human fulfilment is understood to be when a person matures into someone who uses their talents skilfully to participate in a positive way in their community and in the world at large.

Classical pedagogy achieves this human fulfilment in a two-fold way. It pulls you upwards by inspiring you, and it equips you with knowledge and skills to participate in the world. The key words to note here are: inspiring, knowledge andskills.

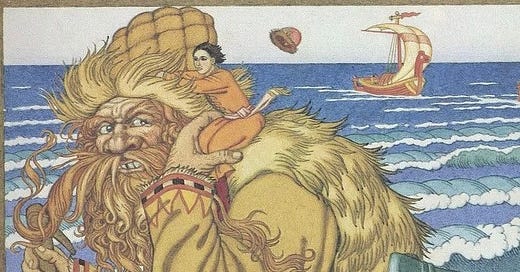

Inspiration is a basic tool used in classical education. It can be understood together with the movement’s motto: the True, the Good and the Beautiful. Classical Education ‘brings what is best’ to its students so as to ‘bring out what is best’ in them. The idea is that children who learn about the great achievements of humanity – intellectual, technological, and spiritual – will be drawn upwards. Their view of what it is possible to achieve will be properly expanded, and a desire will be ignited within them to imitate the greatest achievements. In the same way that children often internalise the limits of achievement they see in their families, they also imitate the limits perceived in their greater family, humanity. Beauty, truth and goodness matter in the Classical school. They inform the content of the curriculum and also act as a teaching methodology.

Content

In the same vein, an important distinctive characteristic of a Classical school is the care given to the content. Content matters.

Let me illustrate this with an example. In our modern schools we tend to place all the emphasis on ‘skills’. In a language arts lesson for example, where children are learning a particular writing skill (say the art of persuasive writing) they might practice the skills (the aims of that day’s lesson) by writing about their favourite Pokémon character. The content of their writing is not the important element of the exercise. It is sufficient to use a character that the children have positive feelings about, such as a popular cartoon figure, to engage the children in the task. What is deemed important are the writing modes that the children are practicing as they write about Pokémon. Similarly, an art class might take inspiration from the game Fortnight that some students play.

In a classical school we would be a lot more careful about the content used to deliver skills learning. The teacher would try to use materials that have some intrinsic value such as educational interest and beauty. The same writing skills for example would be taught by writing about an important historical figure, or a literary figure from a high-quality classic children’s story, or a creature from nature. The content itself would be chosen to be something profitable for the child.

The reason for this is the way children naturally learn. Childhood is a time when children ‘absorb knowledge like sponges.’ This is a common phrase because as is widely acknowledged children are always learning about the world around them. Everything they interact with is a source of information for them about the world they find themselves in.

Children are never just learning a skill or just playing. They are also constantly learning about the world around them. They are forming the schemata with which they will subsequently order facts and discern knowledge for the rest of their life. That is just another way of saying that children form their world view by constantly and eagerly ‘learning’ about the world around them. This world view will form the foundation for how they process knowledge in later years1.

More important than this even is the fact that children are ‘creating themselves’ as they learn about the world. Children are relentlessly learning about the world, but they are also learning about themselves. They are learning who they are in the world. They are forming their view of who they are, what the world is, and from this they are drawing conclusions about what they should be. They are forming the foundation of what they should aspire to become.

While learning about the world they are synthesising the narratives and the frameworks that they will grow into. A lot is at stake with what our world will look like to a child. Children are never just learning skills or just playing. They are involved in a constant praxis of forming themselves. Praxis is the process by which children form theories about the world they find themselves in, and about themselves. They put these theories into practice to test them, refining the theories and the practice in an ongoing feedback loop.

To say that ‘skills matter and the content is not important’ is in fact back to front. It is like saying that we need to exercise our metabolic system by eating but that the nutritional value of the food we eat does not matter. Indeed, the opposite is the case. The value of the skills (reading and writing for example) is to get at the content. The value of our metabolic system is to get nutrition out of (nutritious) food. Likewise, skills are what we use to process knowledge about reality. To seek out understanding, to make sense of it, and to be able to speak our understanding back to our fellows. The content is the valuable part and the skills are processing tools needed for learning, thinking and presenting ideas2.

We want our children to be healthy, so we give them nutritional foods, we do not feed them junk food regularly. Likewise, in the Classical school, the importance of profitable content is recognised. The opportunity cost of turning the mind’s eye towards Pokémon rather than towards the life of swallows (for example) is too high. Schools whose sole purpose of existence is the education and upbringing of the new generations cannot be so casual about the content they regularly expose our children to without becoming absurd institutions - without parents wondering if it wouldn’t be more profitable for their children to stay out of schools and be educated at home.

Indeed, children are ‘serious creatures’. Their time is precious. We often mistake their light-heartedness and their freedom from responsibility for a sort of silliness. It is easy to do great disservice to our children if we engage them with meaningless content. Aiming for better things liberates the child’s innate ability to achieve what seems difficult.

Furthermore, we need to avoid treating children as if they were adults. We need to be more careful with the education of children because children are naturally - since they are forever learning and forming themselves and ‘understanding reality’ – more susceptible. Adults indeed are able to distance themselves from the material they are learning and to approach it more objectively, dissecting it and taking from the experience what is deemed valuable. Adults can do this because their personalities are already formed and they can now focus and be unreceptive to the many facets of an experience.

Children however do not have this distance. Every aspect of the experience leaves its mark on the child. Classical Education respects the children’s nature as natural learners and it values their precious time. It takes up its responsibility - to educate children to be the best that they can be. This is the reason why much care is taken to use content that is profitable – true, good, beautiful and deeply inspiring.

Let us now turn our attention to another sense in which the content of the Classical curriculum is important. So far, we have been speaking about the content and meaning the various materials that are used if you like as the ‘manipulatives’ of the learning process. The stuff that teachers use to deliver the learning of skills. We have been referring for example to the sorts of books used to teach reading, or the sorts of themes used to teach writing or dialogical skills. Now we will turn our discussion to the subject matter that is taught in schools which makes up the ‘content’ of the curriculum in a somewhat different sense of the word.

Classical models are what we call knowledge-based, or knowledge-rich. This means that across the schooling years children learn a prescribed body of knowledge for each subject studied. (read this footnote!3)

Subject matter is taught in the traditional way where students build up a body of core knowledge in key subjects. They map out an overview in each curricular subject (such as maths and science) which gives them the knowledge and context they need to understand and process the concepts of each subject.

Similarly, much attention is given to learning about the past. To the effect that students are enabled to understand themselves and their own societies better, great focus is given to learning about people of the past. A chronological and conceptual overview of the past is studied. Students, already from primary one, learn what people of history did, what happened to them in terms of important historical events, and how they thought (history of ideas).

Children come out of the Classical primary school with a decent overview of local and world history, and with a particularly strong grasp of European history. They also have an informed understanding of local and European culture, and of mathematical and scientific knowledge. They have a foundation of knowledge to understand both their world today and the past that it grew out of.

Methodology

Classical Education methodology is divided into three stages: the Grammar, the Logic and the Rhetoric stages. Each corresponds to a developmental period. Each uses content and teaching methods appropriate to the abilities of the students at the relevant ages.

The Grammar stage roughly corresponds to primary school (elementary). It is based on the premise that younger children are interested in learning how the world is. What is. They are interested in facts about reality. They are gathering knowledge of ‘what’, putting it together and constructing an understanding of what the world is like. Anecdotally we can say that children are always asking ‘what’s that?’. Conveniently young children are also particularly good at memorising facts. Their brain is at its best for absorbing and retaining items of knowledge.

This age group can also be called the ‘trusting’ stage. It is the phase during which children take what others tell them on trust. It is the responsibility of the educators at this point to help children acquire knowledge that is truthful. It is named the Grammar stage because during this phase children are taught the ‘grammar’ of each subject area. The bits of information that amount to the key knowledge of a subject – that laid out together constitute an overview of a subject. Utilizing children’s natural interest and propensity to gather factual descriptive knowledge, the Classical primary school gives children the knowledge they will need to understand the world, and which they will use in later stages to be able to think creatively and critically.

Teaching methodology in the Grammar stage is characterised by the attempt to present knowledge in ways that help children to retain it. The success of the Grammar stage is to deliver the right set of knowledge that will act as the most useful foundation for future learning and thinking.

Let me illustrate this with a characteristic example. The school I am involved in, Saint Andrew’s OC School in Edinburgh, teaches history to primary school children over two sessions per week. The programme of topics covered is fairly extensive. Children who complete the course become familiar with an impressive overview of history, ranging from the earliest recorded history to the 21st century.

The subject matter is taught using a three-year cycle. The first year covers historical empires, peoples and countries. The greatest emphasis is on Ancient Greek and Roman civilizations, but ancient China, early Jewish history, Egyptian civilization and pre-historic people are also covered. The second year teaches pre-reformation to modern world history. The third cycle is dedicated to local history and teaches children the story of Scotland from its Upper Palaeolithic periodup to our own era. At the end of the three years the cycle starts again, and the children study the same topics again. The result is that two of the cycle years are studied twice and one is studied three times.

This repetition enables the students to learn the content-rich material as well as to engage with it meaningfully. The content is taught in an age-appropriate way. The first time that the cycle is taught the children are early primary school age. Once a week the teacher tells the students the lesson as a story. Children love to hear stories. An effort is made to use the captivating force of narrative and the excitement of character arcs to engage the listeners in the story of our ancestors. Following on from this story time, children then interact with the story, making relevant crafts and artwork. Often they play-act the story, telling it back in their own words through theatre. This multi-sensory approach ensures that the children are focused on the learning.

In the second class of the week the children memorise the key points of that week’s lesson (summarised into the length of a short paragraph) in the form of a catchy song or a poem . Once the kids have engaged creatively with the story and have a context for the facts, they use the joy of music to memorise the key facts that we want them to retain. The memorisation of key facts is also supported during the daily revision time where children use a set of enjoyable games, and flashcards to go over their learning (spaced repetition). The purpose is for children to complete their studies at the Grammar stage having become familiar with history, and having thus acquired key knowledge that they will then use as material during the rest of their schooling.

The history classes are also ‘conversational’. In the friendly environment of the small classroom the children are welcome to ask questions about the content, or to make comments about it, both to their teacher and to their peers. Children who are presented with interesting content will often surprise you with the depth of their thought. Their insight and understanding is often profound, even if the language they use to express their meaning is ‘childish’. Presenting children with solid knowledge of historical people and times, problems faced and solutions found, stimulates them to think deeply.

The teacher is alert to any points made by the children which get at significant aspects of the history lesson. They pick up on these and encourage more children to respond to the point made by their classmate. In this way ‘organic child-led’ class discussions occur, with the teacher ensuring that the exchanges are profitable. You might be surprised to see how often, with this simple method, young children become engaged in analysis of the ‘first principles’ of history. At this point children are thinking philosophically. Such meta-discussions however, albeit being welcomed and supported by the teacher to bear fruit, are not structured into the delivery of the class content – which has as its aim to provide children with the facts (the story of history).

Once the children have completed the three-year cycle they start it again, going over the material once more. This time the children are already familiar with the events and historical characters studied. They feel confident that they know something about them already, and thus they are ready to study the material in more depth. The classes might go into more detail about the events, and more time is given to discussions about the relationship of cause and effect. The class makes heavy use of the library finding timelines, old maps, biographical literature and historical stories. Where possible, children go on fieldtrips to visit museums and other sites of historical interest.

Creative interaction through craft and artwork is again used regularly, this time with more attention given to the written word. Themed creative writing and factual report writing are often used in addition to the more physical play-based engagement of the earlier years. The second time the children study the history cycle they engage with more factual detail, in more conceptual depth, as well as with more academic tasks that require more concentrated focus.

During both runs of the history cycle the learning is supported with strong visuals. A long timeline chart is laid out on the floor and a huge map of the world decorates the wall. Each time a new lesson is introduced, or a new character is taught, the students locate them both geographically on the map and on the timeline. This habit, takes less than a minute to do, enables the children to see the connections between the topics they are learning. Additionally, it helps to develop a sense of place, time and era.

When children get to primary 7 the cycle begins again, and they will study one of the years for a third time. At this age the children are transitioning from the Grammar stage of development to the Logic stage. In honour of this the 7th graders engage in much more self-directed study using the library facilities. They are encouraged to ask questions about the content and to use ‘original research’ to answer their queries. This involves a combination of desk-based literary research, interviewing knowledgeable people, and collecting information by visiting sites.

They have regular opportunity to report back the knowledge they have gathered, orally, by making and presenting posters or in written form, to the younger children in the school. The 7th graders learn by teaching and presenting their findings. The younger children, who are also studying the same material, benefit from learning about the specifics that their school peers were excited about. Primary 7 aged children are only able to engage in such learning styles meaningfully because of the cyclical approach of the programme. Having the foundation established in their earlier years, they are familiar enough and adept enough with the course content to be able to deal with it in these more complex ways.

One can see from this example of the history programme that a lot is expected of the children. They are given ‘real’ content to contend with, but the Classical school supports the children to achieve lofty aims joyfully and meaningfully.

The Grammar stage is followed by the Logic stage. It corresponds roughly to middle school. The premise is that round the age of eleven children mature into the phase of asking ‘but why?’ They become interested in cause and effect, in why things are the way they are. They enter a phase where they are sorting out the knowledge that they have, assessing it and understanding more of its complexity.

Here children are methodically encouraged to think critically and analytically. They learn to understand the relationships between different pieces of knowledge and to apply principles of logical reasoning to their studies. Subjects such as formal logic and debate are introduced, and students are taught to question, analyse, and draw conclusions based on the information they have acquired in the Grammar stage. At this point children are equipped and able to apply higher order thinking skills well. Firstly, because they have a foundation of knowledge to fuel these thought processes, and secondly, because they have matured to the point where it is developmentally appropriate for them to do so.

Again, after the Logic stage, children develop into the Rhetoric stage.

Teenagers enter a stage of human development where they become interested in joining society. They let go of the supportive environment that was ‘teaching them’ during their childhood and try to find their own place in the world. Older teenagers are interested in ‘speaking back’, formulating their own thoughts and becoming independent actors in the world they were born into. They want to use the understanding of the world which they have spent their entire life forming and refining to participate in that world and to improve it where they can.

The Rhetoric stage corresponds to the three final years of schooling. Here, students learn to express themselves eloquently and persuasively. Building on the knowledge and analytical skills acquired in the previous stages, students are trained in the art of effective communication. This includes writing essays, giving speeches, and engaging in complex discussions. The goal is for students to be able to articulate their thoughts clearly and persuasively, and to present well-reasoned arguments. I think of this as the ‘creative stage’ since by this point students have ‘understood’ the world enough to begin consciously carving and moulding it anew.

By way of a summary…

Classical education prepares its students to participate responsibly, critically and creatively in their societies. It does this in an orderly manner that respects children’s development – their natural abilities and interests at the different stages. It follows a process – placing knowledge and understanding as the foundational building block for higher order thinking skills, and in this way enables learners to engage with these skills truly.

Besides giving learners the knowledge and skills needed to excel, it also gives them the inspiration to desire what is good, and to aim high. The ethos of Classical schools is to take children seriously, to value their time and to respect them for the incredibly able humans that they are. Truthful content and philosophical depth is preferred over what is mundane or inane. Joy is preferred over superficial immediate gratification. Academic rigour is a value, as well as a methodological tool used to motivate students to achieve excellence.

And that is it for today folks. I intend to go into more depth on various issues raised here in subsequent essays. I hope you are awaiting these with the same excitement that I feel about writing them. I wish you a happy Easter.

This is why we can see a growing awareness about the educative importance of childhood environments. , why there is a political will to define the environment of children, and why family life matters immensely

To be clear skills are also vitally important. Not only do we not mean to downgrade the essentiality of learning skills, but we furthermore hold that skills and content cannot be coherently fully separated. In a forthcoming essay we will discuss the intrinsic link between knowledge, content and skills. For the present moment however we simply want to put skills in their proper place and make it clear that there exists necessary relationship between the three. It is non-sensical to pretend that we can separate skills from content and teach them to children independently.

At this point it is worth pausing to say to my reader. Some of you who do not follow developments in educational theory will likely be thinking ‘of course schools teach a subject knowledge. Children go to schools to learn things, that is obvious, why is it worth noting that the Classical curriculum teaches knowledge?’ To you I would say ‘Alas! Unintuitive as it may seem, one of the bigger changes spawned by the progressive movement is that knowledge has been seriously demoted in the curriculum. In countries where progressive educational ideas have been more wholly embraced (such as New Zealand and Scotland) this lack of knowledge learning is pronounced. We will go into this matter in greater detail in subsequent essays as it is a key difference between classical and progressive models. It is also one of the main reasons why progressive models have failed, despite their best intentions, to deliver the quality of education achieved by traditional schooling.

Those of my readers who read educational theory and are familiar with the debate around knowledge-based curriculums: some of you are thinking ‘yes, exactly, this is what we need!, and some of you are thinking ‘but teaching knowledge is so problematic, this Classical model is perhaps outdated, obsolete and deficient’. To both I would say: over the next few essays I will address issues around the role of knowledge in the curriculum. I hope to not only make a clear case for the significance of learning subject knowledge, but also, to say something about how this is done well (balanced appropriately with the learning of skills). This is a big can of worms as you will know so it will take some detangling of the many arguments before we can do justice to the complexity of the problem.